With Thermal Imaging the Invisible Becomes Visible in a Saddle Fitting Scan

By Becky Tenges, MMCP, CEE, CET, CIT-I

René Descartes once said, “If you can’t taste it, touch it, smell it, hear it or see it – it doesn’t exist”.

If we apply the theory of this very famous 17th Century French philosopher, mathematician and writer to the horse’s back shown in the digital image at left (Image 1), then we would conclude that since we cannot ‘see’ heat, inflammation and/or pain in this photograph, then none of them ‘exist’ in this horse.

Unfortunately, I (and the horse) would have to disagree with Descartes, who by any measure was an intellectual giant. But even so, intellectual giant-hood aside, he is wrong.

So, what is wrong with Descartes’ “if you can’t see it—it doesn’t exist” theory? The answer is that the wrong ‘lens’ is being looked through—the human eye lens (and a digital camera lens) cannot see what the horse would tell you is clearly there.

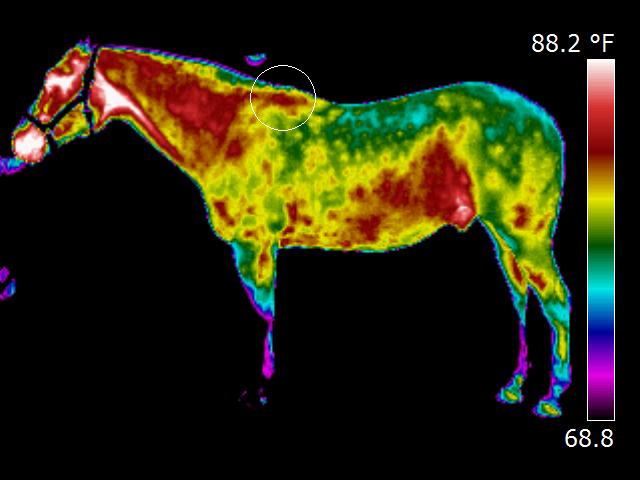

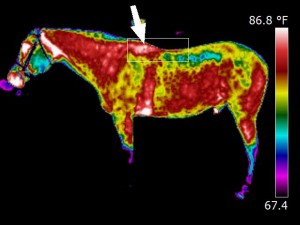

So, what if we ‘changed our lens’? What if we looked at this horse’s back through the lens of an infrared thermal imaging camera, as was done in Image 2? What would we see?

We would see what exists—because with thermal imaging, what is ‘invisible’ to the naked eye, suddenly becomes visible. Hence, in a thermal image, we are permitted to ‘see’—and become aware of—what actually ‘exists’.

With Thermal Imaging, a high-powered infrared detecting camera is used to receive—and translate to visible light—radiant heat rays emitted by an object in order to create a graphic map of the radiant heat coming from the object’s surface. When used to image horses, thermal imaging gives us a visual depiction of underlying circulatory levels of the body, providing us with the ability to ‘see what the horse feels’.

When we take a look at the above horse through the lens of an infrared thermal imaging camera, the view is quite different.

What once appeared to be a lovely, sleek, shiny, healthy back—in a digital image—now is revealed in a thermal image to be a back with heat, inflammation and probable pain.

over the trapezius muscle.

All images in this article (and others taken during this session, but not included here) were taken at the exact same time and with the same specialized, high-powered FLIR T-420 thermal imaging camera. In fact, Image 1 and Image 2 were taken in the same ‘click’ of the camera, which can be set to simultaneously take digital and thermal images. Image 1 has simply been cropped to ‘zero in’ on this horse’s back for this article.

The horse in these images had been exhibiting ongoing back pain. In addition, it was regularly stumbling when asked to pick up a trot and was balky and reluctant when asked to canter. Having worked with her local vet to rule out any soundness issues, the next thing for the owner to check was the saddle.

The owner asked EquineIRTM Certified Thermal Imager, Becky Tenges of Equine BodyWorks, to conduct a Saddle Fit Thermal Imaging Scan. This Saddle Fit scan was done at the horse’s own barn and in accordance with the simple, yet strict, quality control guidelines EquineIR™ has established relating to horse preparation and imaging environment, in order to maximize the quality of the images and minimize the existence and/or influence of artifacts (mud, dirt, sunlight, wind, etc). The Saddle Fit imaging session, which took approximately 45 minutes, included taking images of the sides and top of the horse and the underneath side of the saddle, both before and immediately after the horse was ridden for about 10 minutes.

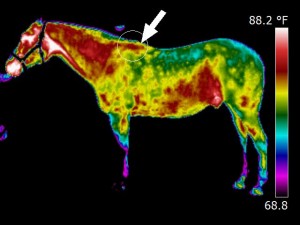

Images 1, 2 and 3 were taken before the horse was ridden. In these ‘before’ images, the reviewing EquineIR™ Network veterinarian, who in addition to being a Certified Level I Thermographer is also a Certified Saddle Fitting Technician, found in her interpretation that the thermal images reveal ongoing inflammation behind the shoulder blades in the area over the trapezius muscles, at the base of the withers, and in the muscles beside the spine. So, the above images reveal the ‘pre-existing’ condition of the horse’s back as a result of prior riding sessions.

So…you might be asking yourself: “If that is what the thermal imaging camera revealed about the horse’s back before it was ridden on this day, what was revealed after it was ridden?”

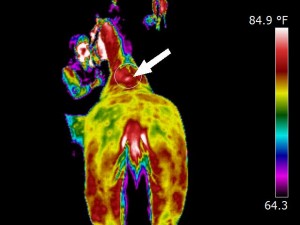

Great question! As you can see below, in the after-riding views, the thermal imaging camera permits us to ‘see even more of what we cannot see’, but which certainly exists.

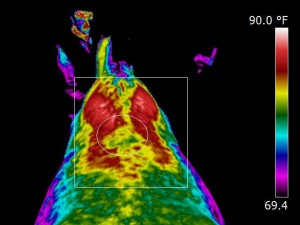

In Image 4, the reviewing veterinarian indicated that the thermal heat patterns suggest this saddle is either being placed too far forward, or is sliding forward on the

horse. The vet also indicated, among other findings, that the thermal images show that there is significant heat (the white areas below the withers where the arrow points), with patterning that suggests that the tree and/or panels are too tight for this broad backed horse, creating pressure at both shoulders.

In Image 5, we can see very clearly the heat patterns being caused by the saddle. As in Image 4, the reviewing EquineIR™ Network veterinarian found in the assessment of Image 5 that the thermal image revealed that the radiated heat patterning suggests that the panels of the saddle are too tight or narrow for this wide horse and are too far forward, impinging on the shoulders (see the boxed area of Image 5 below). In addition, Image 5 shows a slight 1-2” bridge (in the circled area) and then uneven contact with the horse’s back further on where the panels rest on horse.

A typical fitting problem with many saddle designs today is the shape of the bevel (i.e. the roundness or flatness) or the attachment angle of the horizontal panels, as compared to the shape of the horse’s back, whether flat, broad, angled, or round. We can see this panel-shape-versus-horse-shape challenge on this horse’s broad, flat, barrel-shaped back by virtue of the fact that there is not a uniform pattern of heat where the rear sections of the panels make contact with the horse.

But what does this actually mean…to the horse? To put this in terms that we might more readily relate to, imagine that you are standing on one of your feet, barefooted on a 4×4 section of wood. Now, rather than standing flat-footed, evenly distributing your weight across the four-inch width and the entire bottom of your foot, imagine that you shifted your foot and weight such that you were now standing crookedly—and with all of your weight only on the edge of the wood. This now means that all of your weight is now being pressed down through only the very narrow portion of your foot that is in contact with the wood’s edge—perhaps a 1/3 inch wide area.

Ouch! It’s simple physics—the greater the size of the area across which we distribute weight, the more comfortable—i.e. the less painful—it will be.

When we look at Image 6 which shows the thermal image of the under-side of the saddle post-riding, we can perhaps see even more vividly the challenges that this saddle poses for the horse, in the tightness in the shoulders, the bridging where it loses contact in the middle (at the white arrows) and in the fact that only the edges of the horizontal panels are contacting the horse’s back toward the rear of the panels.

In the lower part of Image 6, in the boxed area, the forward section of the panels shows red- and white-hot (the hottest) thermal heat patterns—exactly in the location where the impingement is occurring that we saw above, in Image 5 of the horse’s back and shoulders.

At the top of Image 6 (in the circle), we see a rainbow of colors at the rear of the panels, where the color shifts from deep red in the center of the panel to black at the inside edges represents a decrease in thermal heat patterns. What should appear as a uniform redness of equal width and intensity across the panels, in this case, actually appears as a cascade of colors, that range from red to green, blue to purple and, finally, to black, in the area where the panels are not touching the horse’s back at all, which creates the optical illusion that the saddle’s channel width is wider at the rear than in the front. The channel of this saddle does not widen out from front to back—it just stops making contact because the rounded bevel of the saddle does not permit the entire panel to rest upon this horse’s flat, barrel-shaped back. (At this point, you might be reflecting on that 4×4-vs-foot activity above…and you might be ‘feeling’, sympathetically at least, discomfort in your foot. No worries. Descartes gets this one correct—that pain in your foot doesn’t really exist).

Obviously, with the ‘visibility’ provided by the thermal images taken during this Saddle Fit scan, this horse’s owner was able to see what had previously been invisible. She has ordered a new saddle. It should arrive soon! And we now have another happy pony and one more horse-owner who obtained answers because of equine thermal imaging!

So, here’s the bottom line: Descartes truly was wrong…he just couldn’t see it. You can trust what you see (or what you believe ought to be seen), even if smarter, brainier folks tell you it doesn’t exist. You just have to be looking through the correct lens. And, if you are using thermal imaging, you can trust what is revealed…provided you are using technicians and reviewing

enables us to see several saddle fit issues

veterinarians certified in the sciences of thermography and equine thermography…like those professionals who are members of the EquineIR™ Network.

—————————–

Becky Tenges, MMCP, CEE, CET, CIT-I is the owner of Equine BodyWorks and a proud member of the EquineIR™ Network. Becky’s focus is to provide therapeutic relief to her equine clients and information and answers to their owners and trainers using Equine Thermal Imaging, Performance Bodywork and Saddle Fit Services. With the bodywork and diagnostic services Becky offers, she brings straightforward methodologies and a heartfelt dedication to Revealing Afflictions, Reducing Discomfort and Enhancing Movement & Performance™. Becky can be reached through her website at www.EquineBodyWorksUSA.com.